Inside the Transformer: Attention Mechanisms Deep Dive

Understanding What Happens Inside Each Layer

What We’ll Cover

In Post 1, we understood why Transformers emerged and the basic attention formula.

Now we’re going deeper:

What actually happens inside a single Transformer layer?

How do attention patterns evolve across layers?

What’s the role of feed-forward networks?

How does information flow through the entire architecture?

What are the practical engineering choices that matter?

By the end, you’ll understand:

Why Transformers have residual connections everywhere

What layer normalization actually does

How positional information propagates

The difference between encoder and decoder attention patterns

Why certain architectural choices (like pre-norm vs post-norm) matter

Let’s dive in.

1. Anatomy of a Transformer Layer

Here’s what most tutorials show you:

Input → Self-Attention → Add & Norm → Feed-Forward → Add & Norm → Output

Here’s what actually happens (and why each piece matters):

1.1 The Complete Picture

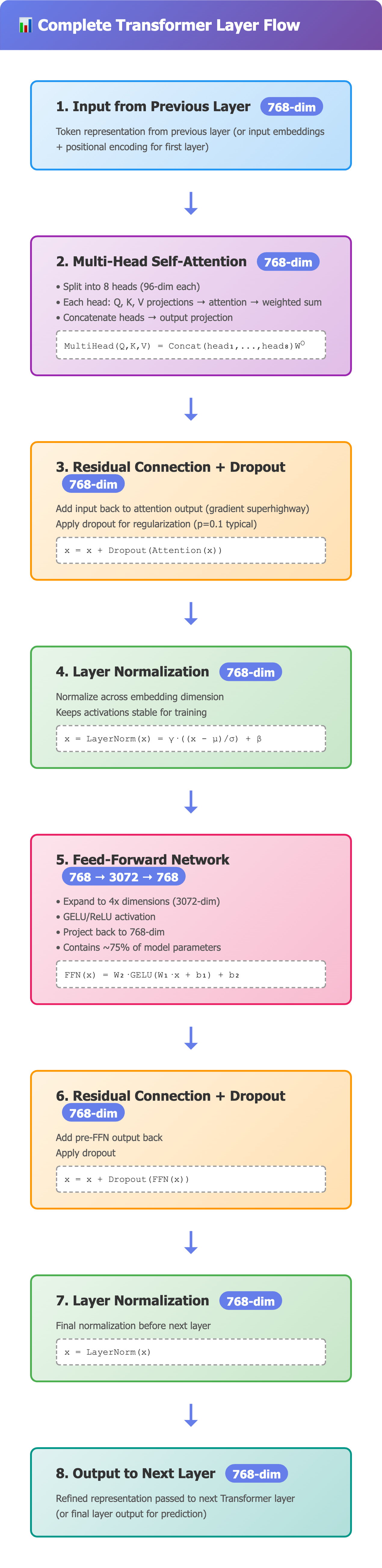

A single Transformer layer has six distinct operations:

1. Input (from previous layer or embeddings)

2. Multi-Head Self-Attention

3. Residual Connection + Dropout

4. Layer Normalization

5. Position-wise Feed-Forward Network

6. Residual Connection + Dropout + Layer Normalization

Let’s break down each component and understand why it exists.

2. Self-Attention: Beyond the Formula

In Post 1, we covered the math. Now let’s understand what it’s actually computing.

2.1 The Three Projections: Why QKV?

Every token starts as an embedding vector (say, 768 dimensions for BERT).

We project it into three different spaces:

Q = input @ W_Q # Query: “What am I searching for?”

K = input @ W_K # Key: “What am I advertising?”

V = input @ W_V # Value: “What content do I provide?”

Why separate projections?

Think of it like a search engine:

Query (Q): Your search terms

Key (K): Document titles/metadata

Value (V): Document content

You match Q with K (relevance), then retrieve V (content).

The non-obvious insight: Q and K live in the same space (for dot product), but V can be in a completely different space. This separation is crucial for learning.

2.2 What Attention Scores Actually Represent

When we compute score = Q · K^T / √d_k, we’re asking:

“How much should token i care about token j?”

But here’s what’s not obvious: these scores are relative, not absolute.

After softmax, the attention distribution must sum to 1. This means:

High attention to one token → necessarily lower attention to others

Attention is a resource allocation problem

The model learns what to ignore as much as what to attend to

Example:

Sentence: “The cat sat on the mat”

Token “sat” attention: [0.05, 0.42, 0.15, 0.18, 0.08, 0.12]

The 0.42 to “cat” isn’t meaningful in isolation ,it’s meaningful because it’s much higher than 0.05 to “The” and 0.08 to “the”.

2.3 Attention Patterns Across Layers

Here’s something researchers discovered by visualizing attention in trained models:

Early layers (1-4):

Focus on local, syntactic patterns

Adjacent token attention is high

Learn basic grammar (noun-verb, determiner-noun)

Middle layers (5-8):

Learn semantic relationships

Longer-range dependencies emerge

Capture coreference, entity relationships

Late layers (9-12):

Task-specific patterns

Very focused attention (sparse patterns)

Often just propagating information

This hierarchical learning wasn’t explicitly programmed it emerged from training

2.4 The Mystery of Attention Heads

In an 8-head attention setup, here’s what researchers found heads learn:

Head 1: Might attend to the next token (positional)

Head 2: Might attend to the previous token (positional)

Head 3: Might attend to sentence boundaries

Head 4: Might focus on verbs when processing subjects

Head 5: Might track coreference (”it” → “cat”) Head 6-8: Often less interpretable, learning complex patterns

The controversial part: Not all heads are equally important. Some heads can be pruned with minimal performance loss.

Why keep 8 heads then? Redundancy and specialization.

During training, different heads explore different patterns. By the end, some become critical, others provide insurance.

3. Layer Normalization: The Unsung Hero

Layer normalization is often treated as a boring implementation detail. It’s not. It’s critical to making Transformers trainable.

3.1 What It Does

For each token, independently:

mean = x.mean(dim=-1, keepdim=True)

std = x.std(dim=-1, keepdim=True)

x_norm = (x - mean) / (std + epsilon)

output = gamma * x_norm + beta # Learnable parameters

This normalizes across the embedding dimension (not across the batch or sequence).

3.2 Why It Matters

Problem without LayerNorm:

As you stack layers, activations can grow or shrink dramatically. By layer 12, some dimensions might be 100x larger than others. This creates:

Gradient instability

Difficulty in learning

Slow convergence

LayerNorm fixes this by keeping activations in a stable range.

3.3 Pre-Norm vs Post-Norm

This is one of those details that matters more than you’d think.

Post-Norm (Original Transformer):

x = LayerNorm(x + SelfAttention(x))

x = LayerNorm(x + FFN(x))

Pre-Norm (Modern LLMs like GPT-3):

x = x + SelfAttention(LayerNorm(x))

x = x + FFN(LayerNorm(x))

Why Pre-Norm won:

Gradient flow: Cleaner gradient path through residual connections

Stability: Easier to train very deep models (100+ layers)

No warm-up needed: Can use higher learning rates from the start

GPT-3, LLaMA, and most modern LLMs use Pre-Norm.

4. Residual Connections: Why They’re Everywhere

Every Transformer layer has two residual connections:

x = x + SelfAttention(x)

x = x + FeedForward(x)

4.1 The Gradient Superhighway

Without residual connections, the gradient for layer 1 would need to flow through:

12 self-attention blocks

12 feed-forward blocks

24 normalizations

That’s 48+ operations. Gradients would vanish.

With residual connections: The gradient can flow directly from output to input, bypassing all intermediate operations.

Think of it as:

Residual path: Gradient superhighway (direct route)

Attention/FFN path: Side roads (optional detours)

The model learns deltas (changes) rather than full transformations.

4.2 What Residual Streams Actually Learn

Here’s a mental model that helps:

Each layer adds a small update:

Layer 1: base_representation + small_update_1

Layer 2: base_representation + small_update_1 + small_update_2

...

Layer 12: base_representation + Σ(all updates)

Early layers can learn low-level features, later layers refine them, and all information is preserved through the residual stream.

This is why Transformers can be so deep , each layer makes a small, additive contribution.

5. Feed-Forward Networks: The Hidden Workhorse

After attention, every layer has a position-wise feed-forward network:

FFN(x) = max(0, x @ W1 + b1) @ W2 + b2

Two linear layers with a ReLU in between.

5.1 Why Do We Need FFN After Attention?

Attention is great at routing information between tokens. But it’s terrible at transforming that information.

Attention: “Gather relevant info from other tokens” FFN: “Process and transform that gathered info”

Think of it as:

Attention: Communication between tokens

FFN: Computation within each token

5.2 The Hidden Dimension Expansion

Here’s a key detail: the FFN has a hidden dimension that’s 4x larger than the model dimension.

For a model with d=768:

Input: 768 dimensions

Hidden layer: 3072 dimensions (4x expansion)

Output: 768 dimensions

Why expand then compress?

The expansion gives the model expressive capacity. It can compute complex, non-linear transformations in that higher-dimensional space.

Analogy: It’s like spreading out your work on a large table (3072-dim space) to do complex operations, then neatly packing it back into a small box (768-dim).

5.3 Where Parameters Live

Here’s a surprise: Most parameters are in the FFN, not attention.

For BERT-base (110M parameters):

Attention: ~25M parameters (22%)

FFN: ~75M parameters (68%)

Embeddings + other: ~10M parameters (10%)

The FFN is doing most of the heavy lifting in terms of parameter count.

6. Complete Layer Flow: Putting It All Together

Let’s trace a single token through one Transformer layer:

1. Input: [768-dim vector]

2. Multi-Head Attention:

- Split into 8 heads (96-dim each)

- Each head: Q, K, V projections → attention → weighted sum

- Concatenate 8 heads back to 768-dim

- Output projection

3. Residual + Dropout:

- Add input to attention output

- Apply dropout (random zero out during training)

4. Layer Norm:

- Normalize across 768 dimensions

5. Feed-Forward:

- Project to 3072-dim

- ReLU activation

- Project back to 768-dim

6. Residual + Dropout + Layer Norm:

- Add previous output to FFN output

- Apply dropout

- Normalize

7. Output: [768-dim vector] → fed into next layer

Key insight: The vector stays 768-dimensional throughout. It’s continuously being:

Mixed with other tokens (attention)

Transformed (FFN)

Refined (layer norm)

Preserved (residual connections)

7. Positional Information: How It Propagates

In Post 1, we added positional encodings at the input. But here’s the question: how does position information survive through 12 layers?

7.1 Positional Encodings Don’t Disappear

Once added at the input, positional information flows through:

Residual connections: Preserve the original positional signal

Attention: Can learn position-dependent patterns (e.g., “pay more attention to nearby tokens”)

FFN: Can condition transformations on position

The model learns to use positional information, but it’s not forced to.

7.2 Modern Alternatives: RoPE (Rotary Position Embeddings)

Models like LLaMA use RoPE instead of sinusoidal encodings.

Key difference:

Sinusoidal: Add position info to embeddings

RoPE: Rotate Q and K vectors based on position

Why RoPE is better:

Position info is baked into the attention mechanism itself

Better extrapolation to longer sequences

Relative position is more naturally represented

Formula (simplified):

Q_rotated = rotate(Q, position_m)

K_rotated = rotate(K, position_n)

attention_score = Q_rotated · K_rotated^T

The dot product automatically captures relative position (m - n).

8. Encoder vs Decoder: Attention Pattern Differences

8.1 Encoder (BERT-style): Bidirectional Attention

Every token can attend to every other token, including future tokens.

“The cat sat on the mat”

“cat” can attend to: [The, cat, sat, on, the, mat]

Use case: Understanding tasks (classification, NER, Q&A) You need full context to understand meaning.

8.2 Decoder (GPT-style): Causal Attention

Token i can only attend to tokens 1...i (no peeking at future).

This is enforced via an attention mask:

Attention mask (lower triangular):

1 0 0 0 0 0

1 1 0 0 0 0

1 1 1 0 0 0

1 1 1 1 0 0

1 1 1 1 1 0

1 1 1 1 1 1

Before softmax, we set masked positions to -∞, so they get zero attention.

Why causal? For autoregressive generation (predicting next token), the model shouldn’t cheat by looking ahead.

8.3 Encoder-Decoder (T5-style): Cross-Attention

Decoder attends to encoder outputs:

Encoder: Processes input bidirectionally

Decoder:

- Self-attention (causal) on output tokens

- Cross-attention to encoder outputs

- Generates output autoregressively

Cross-attention mechanism:

Q: From decoder

K, V: From encoder outputs

This allows the decoder to “look at” the input while generating output.

9. What Makes Attention “Learn”?

9.1 Attention is Learned, Not Programmed

The matrices W^Q, W^K, W^V are learned through backpropagation.

Initially (random initialization):

Attention is nearly uniform

All tokens attend equally to all others

Model is useless

During training:

Gradients flow through attention scores

Model learns: “When I see X, attend strongly to Y”

Useful patterns emerge

The model discovers that:

Verbs should attend to subjects

Pronouns should attend to their referents

Adjectives should attend to nouns

etc.

None of this is hardcoded.

9.2 The Softmax Bottleneck

Here’s a limitation not often discussed:

Softmax forces attention to be a probability distribution (sums to 1).

This creates a bottleneck:

If you need to attend strongly to 5 tokens, each gets ~0.2 attention

If you need to attend to 1 token, it gets ~1.0 attention

For very long sequences, this becomes problematic. You might need information from 10 different tokens, but softmax forces you to distribute attention thinly.

Solutions in research:

Sparse attention (attend to subsets)

Multi-query attention (share K, V across heads)

Attention alternatives (Mamba, RWKV)

10. Engineering Choices That Matter

10.1 Dropout Placement

Dropout is applied in three places:

After attention output projection

After FFN output projection

Sometimes on attention weights themselves

Why? Regularization. Prevents overfitting by randomly dropping connections during training.

Typical values: 0.1 (drop 10% of activations)

10.2 Activation Functions

Original Transformer: ReLU in FFN Modern LLMs: GELU (Gaussian Error Linear Unit) or SwiGLU

Why GELU?

Smoother gradients

Better empirical performance

Used in BERT, GPT-3, etc.

Formula:

GELU(x) = x * Φ(x) where Φ is Gaussian CDF

Approximately: 0.5 * x * (1 + tanh(√(2/π) * (x + 0.044715 * x³)))

10.3 Initialization

Getting initialization right is crucial:

Xavier/Glorot initialization:

W ~ N(0, 2/(d_in + d_out))

Why it matters:

Too small → vanishing activations

Too large → exploding activations

Modern Transformers often use scaled initialization where deeper layers get smaller initial weights.

10.4 Learning Rate Schedules

Warmup + Decay:

1. Linear warmup: 0 → max_lr (first 4000-10000 steps)

2. Inverse square root decay: lr ∝ 1/√step

Why warmup? Early in training, large gradients can destabilize the model. Warmup lets the model “settle” before full-speed training.

11. Visualizing Attention: What Works, What Doesn’t

11.1 Attention Heatmaps

Common visualization: plot attention weights as a matrix.

What it shows: Which tokens attend to which What it doesn’t show: What information is actually extracted

Limitation: High attention ≠ high importance for the final prediction

11.2 Better Interpretability Methods

1. Attention Rollout Combine attention across layers to see end-to-end paths

2. Gradient-based Attribution Which tokens, when changed, most affect the output?

3. Probing Classifiers Train simple classifiers on layer outputs to see what information is encoded

4. Causal Interventions Ablate specific attention heads and measure impact

12. Common Misconceptions Revisited

Misconception #1: “Each layer builds higher-level features”

Reality: Not always hierarchical. Later layers sometimes undo earlier work or route around it via residual connections.

Misconception #2: “More heads = better”

Reality: Diminishing returns. 16 heads isn’t 2x better than 8. Some research shows 4-8 heads is a sweet spot.

Misconception #3: “Attention does all the work”

Reality: FFN has 3x more parameters and is equally critical. Attention routes information; FFN processes it.

Misconception #4: “Layer norm is just a regularization trick”

Reality: It’s fundamental to training stability. Without it, deep Transformers are nearly untrainable.

13. Interview Deep-Dive: Architecture Questions

Q1: Walk me through one forward pass of a Transformer layer.

Answer:

Input (d-dim) → Multi-head attention

Add input back (residual) → Layer norm

FFN: d → 4d → d with ReLU

Add previous output (residual) → Layer norm

Output passed to next layer

Key: Residual connections provide gradient paths; layer norm stabilizes training.

Q2: Why do we need separate Q, K, V projections?

Answer: Attention is computing a weighted sum. Q and K determine weights (via dot product), V provides content. Separating them gives the model flexibility: relevance (Q·K) and content (V) can be learned independently. If we used the same projection, attention would be symmetric and less expressive.

Q3: What’s the purpose of the FFN after attention?

Answer: Attention is linear in content (weighted sum). FFN adds non-linearity and transformation capacity. Attention routes information between tokens; FFN processes information within each token. Without FFN, the model would be limited to linear combinations.

Q4: Pre-norm vs post-norm, which is better and why?

Answer: Pre-norm is better for deep models:

Cleaner gradient flow through residuals

More stable training (no warmup needed)

Used in GPT-3, LLaMA, modern LLMs

Post-norm was original design but struggles with very deep models (>24 layers).

Q5: How does positional information propagate through layers?

Answer: Added at input, then:

Residual connections preserve original positional encodings

Attention can learn position-dependent patterns

Model learns to use or ignore position as needed per layer

Modern approach (RoPE): Rotate Q/K based on position, baking positional info into attention mechanism directly.

Q6: What happens during causal masking in decoder attention?

Answer: Before softmax, set future positions to -∞:

scores = QK^T / √d_k

scores[i, j] = -∞ where j > i # Mask future

attention = softmax(scores) # Future positions → 0

This prevents token i from attending to tokens after position i, enforcing autoregressive property.

Q7: Why is √d_k important in scaled dot-product attention?

Answer: Dot product magnitude grows with dimension. For d_k = 512, unscaled dot products can be large (±50), pushing softmax into saturation (extreme outputs like 0.0001, 0.9998). This kills gradients.

Dividing by √d_k normalizes variance to ~1, keeping softmax in its “soft” regime where gradients are healthy. Critical for trainability.

Q8: How much compute does self-attention use vs FFN?

Answer: Per layer for sequence length n, model dim d:

Self-attention: O(n² · d) for attention matrix + O(n · d²) for projections

FFN: O(n · d²) typically (d → 4d → d)

For short sequences (n < d), FFN dominates compute. For long sequences (n > d), attention dominates.

In practice: FFN has 3x more parameters but attention has quadratic complexity in n.

Q9: Can you remove attention heads without hurting performance?

Answer: Yes, to some extent. Research shows:

Some heads are redundant (10-20% can be pruned)

But most heads contribute something unique

Pruning requires careful analysis (can’t just randomly remove)

Some tasks more sensitive than others

Suggests multi-head attention has useful redundancy but isn’t wasteful.

Q10: What’s the memory bottleneck during inference?

Answer: KV cache. For autoregressive generation:

Store K, V for all previous tokens

At each step, attend to cached K, V

Memory: O(n · layers · d) per sequence For 2K context, 32 layers, d=4096: ~1GB per request

This is why context length is expensive—it’s primarily a memory problem, not compute.

14. Practical Takeaways

For Building Systems:

Pre-norm architecture for new models (better training stability)

GELU/SwiGLU activations over ReLU (better performance)

RoPE positional encoding for better extrapolation (used in LLaMA)

FlashAttention for memory-efficient training (3x faster, 10x less memory)

Gradient checkpointing to trade compute for memory

For Understanding Models:

Attention patterns evolve across layers (syntactic → semantic → task-specific)

FFN does most computation (3x more parameters than attention)

Residual connections are critical for gradient flow

Not all attention heads are equal (some can be pruned)

Position information propagates via residuals and attention

For Debugging:

Check attention entropy (low = too focused, high = too uniform)

Visualize attention rollout for multi-layer paths

Monitor gradient norms (residuals help, but explosions still happen)

Probe intermediate layers to see what’s learned where

Ablate heads/layers to find critical components

✨ The Bigger Picture

Understanding Transformer internals isn’t just academic ,it’s practical:

For research:

Know what to modify (attention alternatives, FFN variants)

Understand scaling properties

Debug training issues

For engineering:

Optimize inference (KV cache, attention kernels)

Choose architectures (encoder vs decoder)

Tune hyperparameters meaningfully

For product:

Understand capabilities and limitations

Make informed model selection

Predict behavior on edge cases

Every layer refines the representation a bit more. Every attention head captures a different pattern. Every residual connection preserves information flow.

The beauty is in how simple components compose into powerful systems.

📚 References & Further Reading

🔹 Foundational & Core Attention Papers

Bahdanau et al. (2014) – Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate

https://arxiv.org/abs/1409.0473Luong et al. (2015) – Effective Approaches to Attention-based Neural Machine Translation

https://arxiv.org/abs/1508.04025Vaswani et al. (2017) – Attention Is All You Need (for multi-head attention formalization)

https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762

🔹 Technical Deep Dives & Visual Guides

Jay Alammar – The Illustrated Attention

https://jalammar.github.io/visualizing-neural-machine-translation-mechanisms-and-attention/The Illustrated Transformer (Attention section)

https://jalammar.github.io/illustrated-transformer/Lilian Weng – Attention? Attention!

https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2018-06-24-attention/Harvard NLP – Annotated Transformer (Attention code walkthrough)

http://nlp.seas.harvard.edu/annotated-transformer/Peter Bloem – Transformers from Scratch (detailed math on attention)

https://peterbloem.nl/blog/transformers

🔹 Research & Variants of Attention

Sparse Transformers (OpenAI, 2019)

https://arxiv.org/abs/1904.10509Performer: Linear Attention (Choromanski et al., 2020)

https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.14794Longformer (Beltagy et al., 2020) – Local + Global attention pattern

https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.05150Linformer (Wang et al., 2020) – Low-rank self-attention

https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.04768

🔹 Videos & Talks

Yannic Kilcher – Attention Mechanisms Explained

Andrew Ng – Self-Attention Explanation (DeepLearning.AI)

MIT 6.S191 – Lecture on Attention Mechanisms

Karpathy – “Let’s Build Attention From Scratch” (implicit in GPT lecture)

What’s Next?

This post covered what happens inside a Transformer.

Next in the series:

Post 3: Scaling Laws & Training LLMs

Post 4: Alignment & Production

If this deep-dive was valuable, share it with someone learning ML. This series documents everything I wish I understood when building with Transformers.